Since 2015, I have sewn 3D paper assemblages (and their resulting images) from printed photographs I have taken in places I have lived and visited. As an Asian-American human, I identify as being of the diaspora and a product of assimilation culture. I believe what we see around us—the landscape and buildings, the types of labor and activities, the aesthetic and technological choices and conditions—plays a role in who we are while our lineages inform how we make sense of it all. I have lived my life walking and weaving within urban spaces of the US while psychologically contending with generational traumas, motherlands (China and Japan) as simultaneously foreign and integrated, and my own position within histories of speculation, hierarchical race creation and colonialism. By photographing and sewing together places from all over the world that I have occupied or inhabited, I create sculptures honoring the manifestations of histories, shared needs, connected conditions. The resulting sculptures are psychogeographic maps that miniaturize and deconstruct structured space—a product of human labor, the authority of financialization, and modern survival.

The themes that connect my work are the toxic—and ultimately futile—desire for control and the resulting hierarchical structures that are borne from human fear and trauma. The amalgamation of twisted and contorted images of human-built interventions displayed on delicate, biodegradable material speaks both to the fragility of our physical world and to the swirl of emotions and ideas entangled in our complex society. The placements of these objects, in both real and distorted manners into public and infrastructural landscapes, ask the viewer to consider the details of their surroundings, the inequitable structures that provide our everyday lives, and that our attempts to control each other and our environments are at the core of the crisis.

20XX was the first series of photographs of these objects placed within (mostly) public locations within my hometown area of the East Bay. Construct is the subsequent series in which the sculptures are digitally installed in personal and literal infrastructural locations.

In 2021, I started the series Season First/Finale, Episode Attuned, which are smaller vignette sculptures. In 2022, I completed a series of large-scale hanging sculptures, MOMENTOus, made of the deconstructed—and then reconstructed—sculptures photographed within the images of 20XX.

Photo-Based Sculpture Series

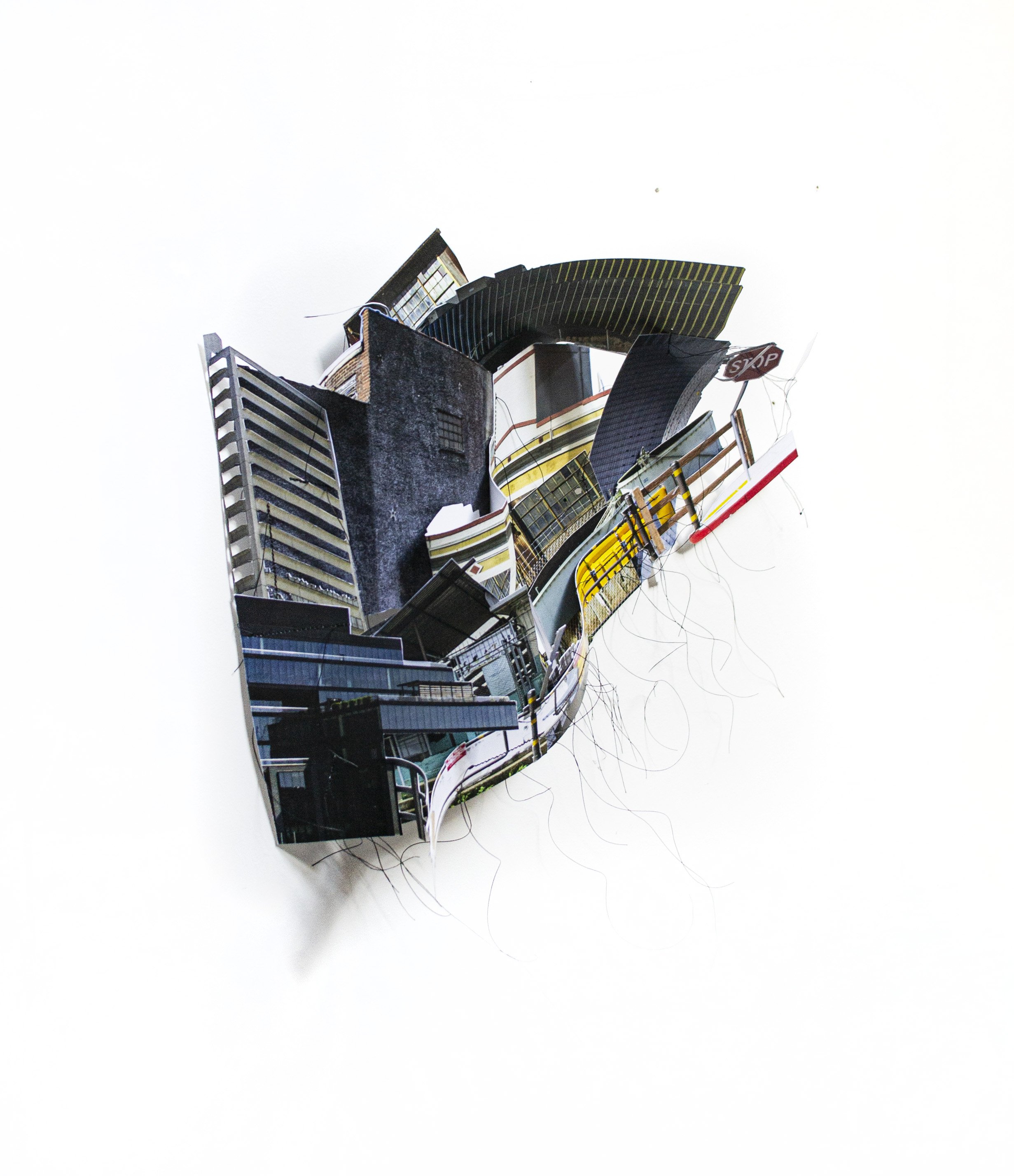

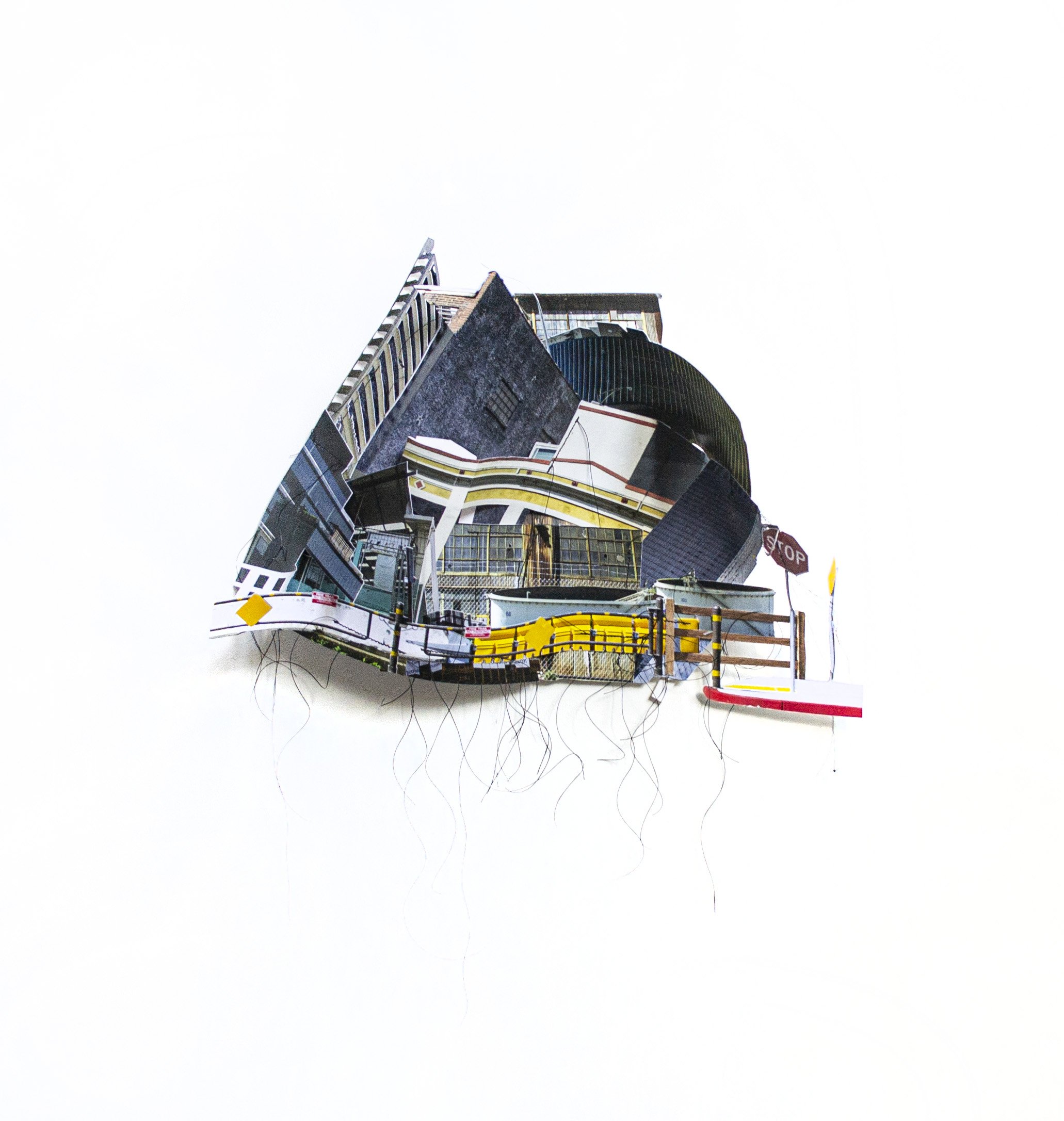

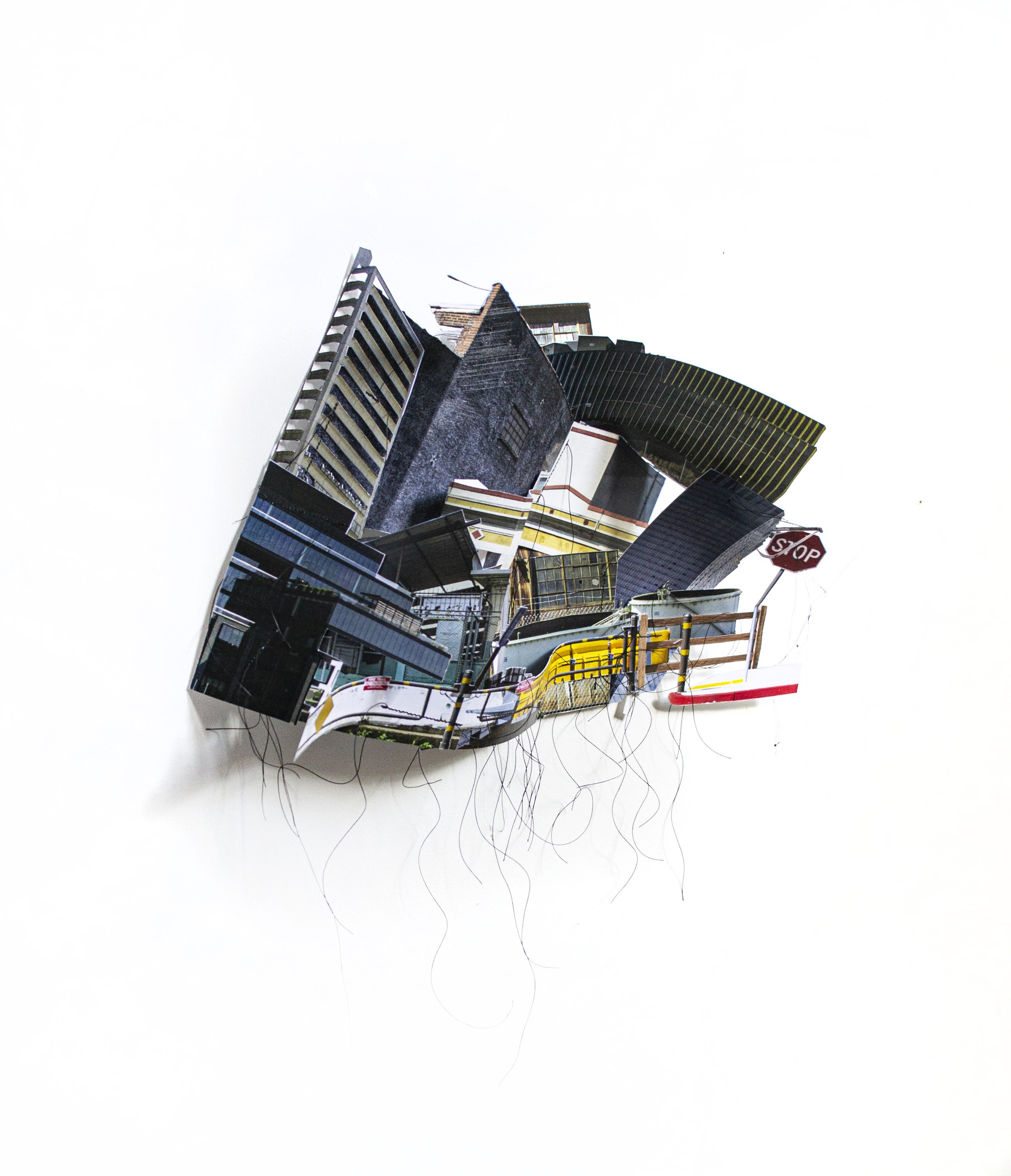

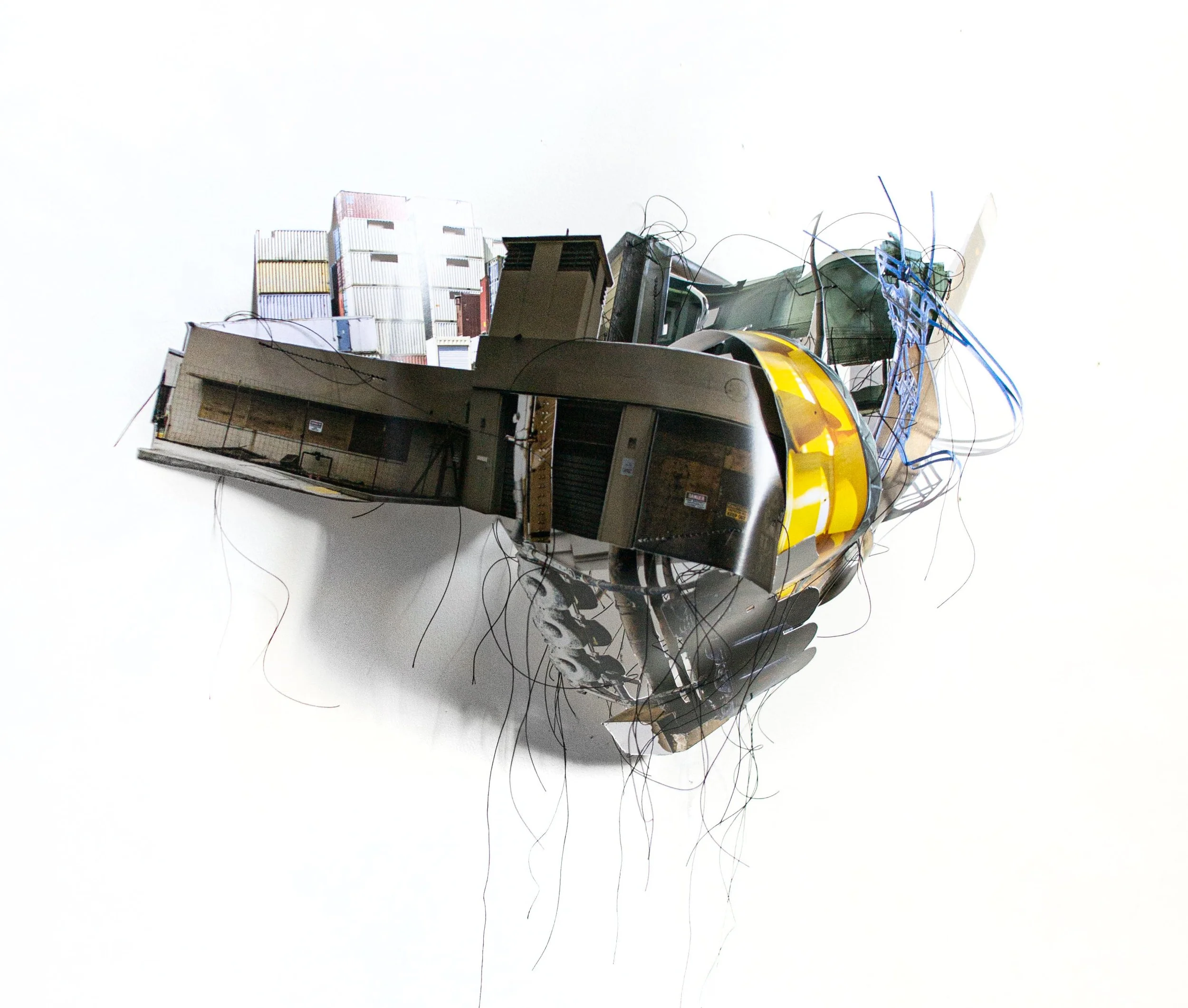

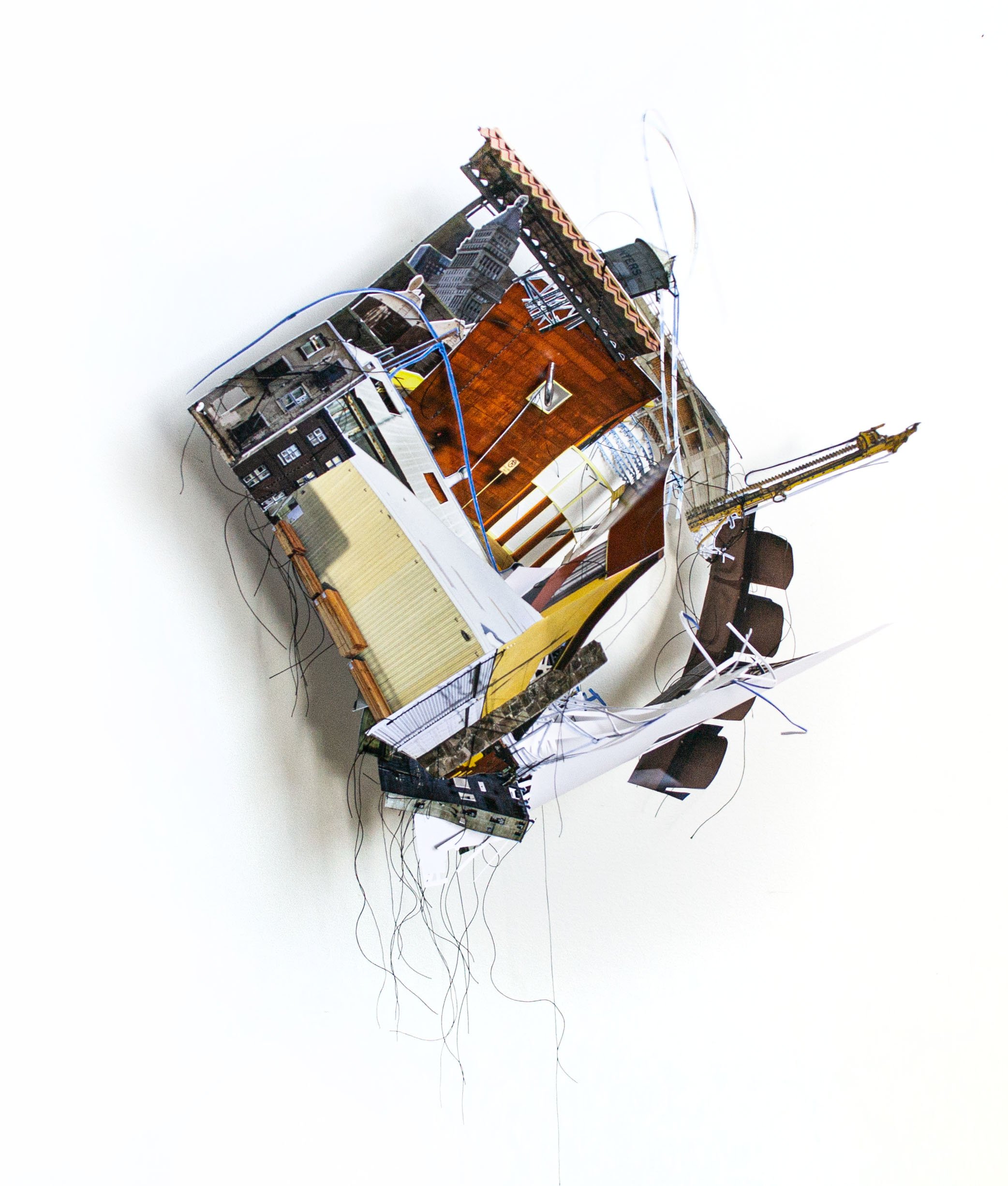

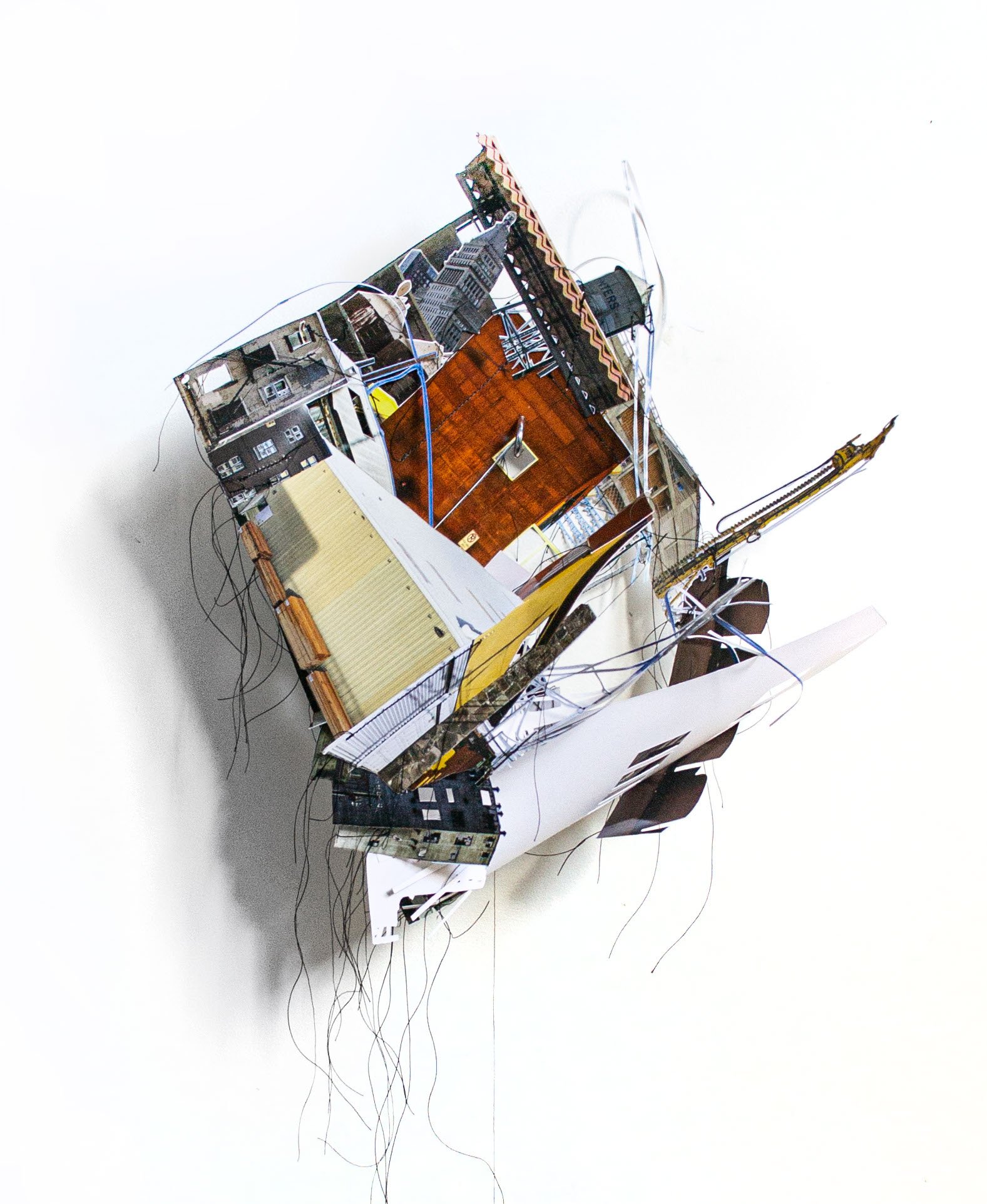

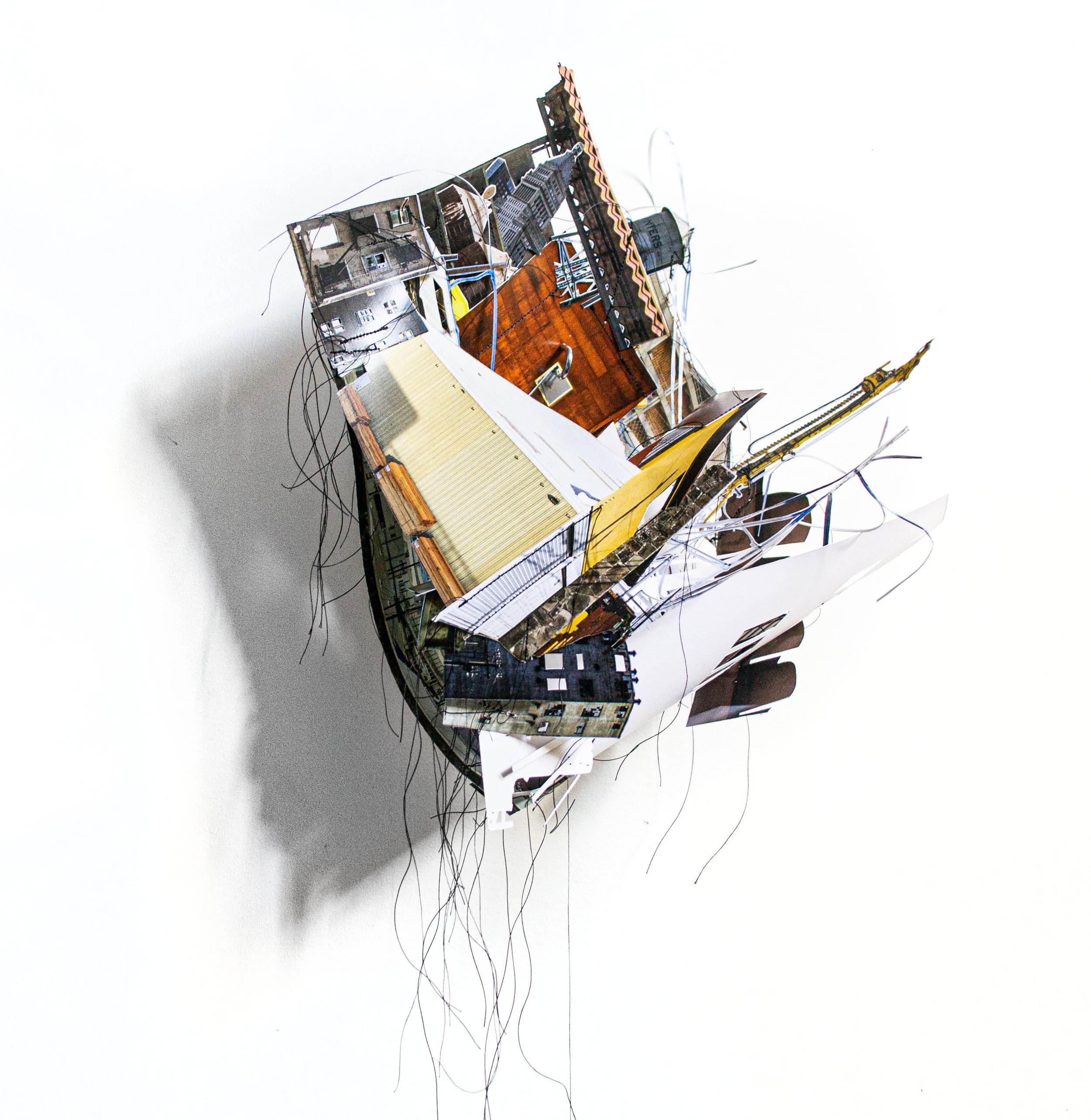

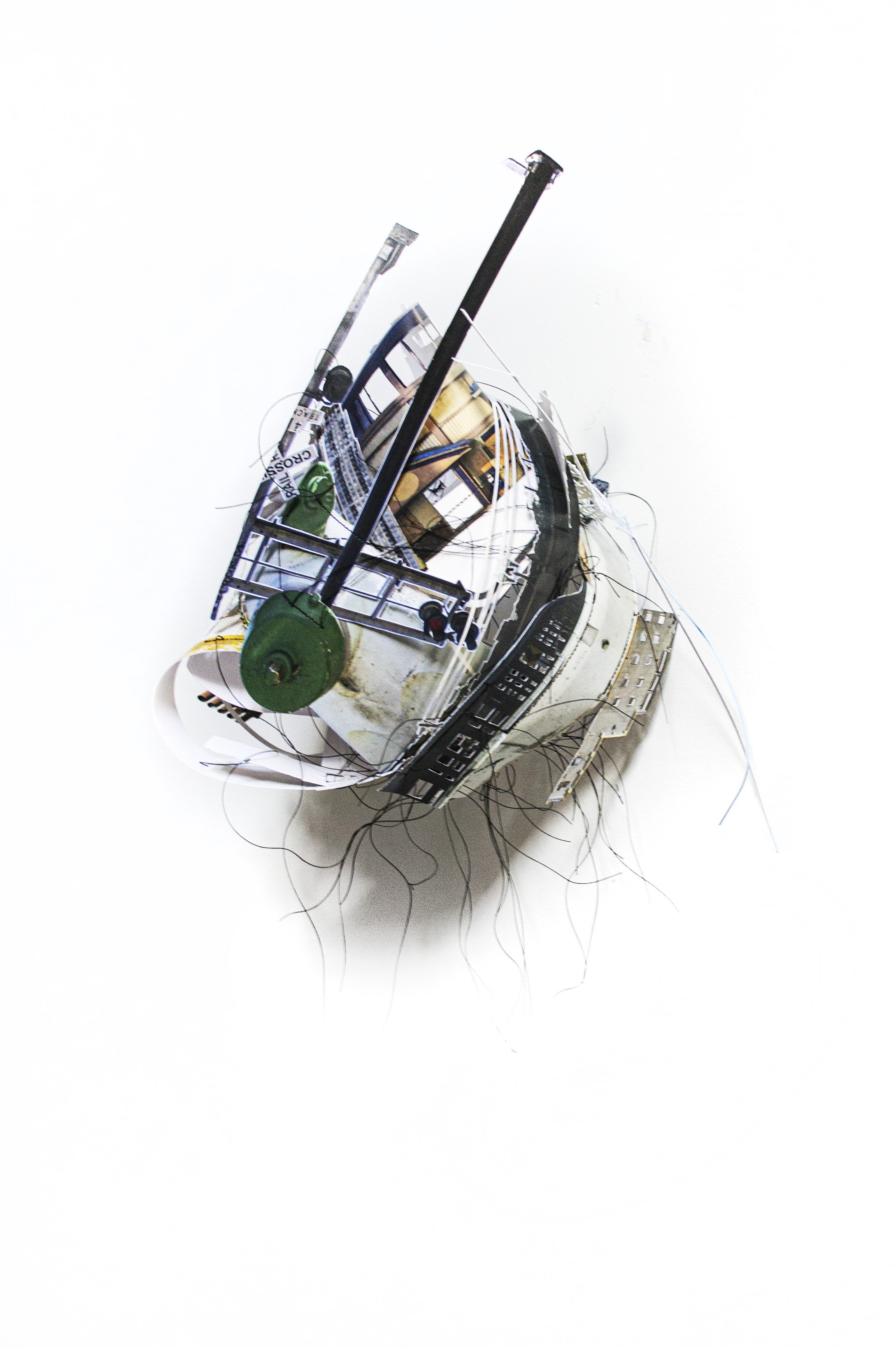

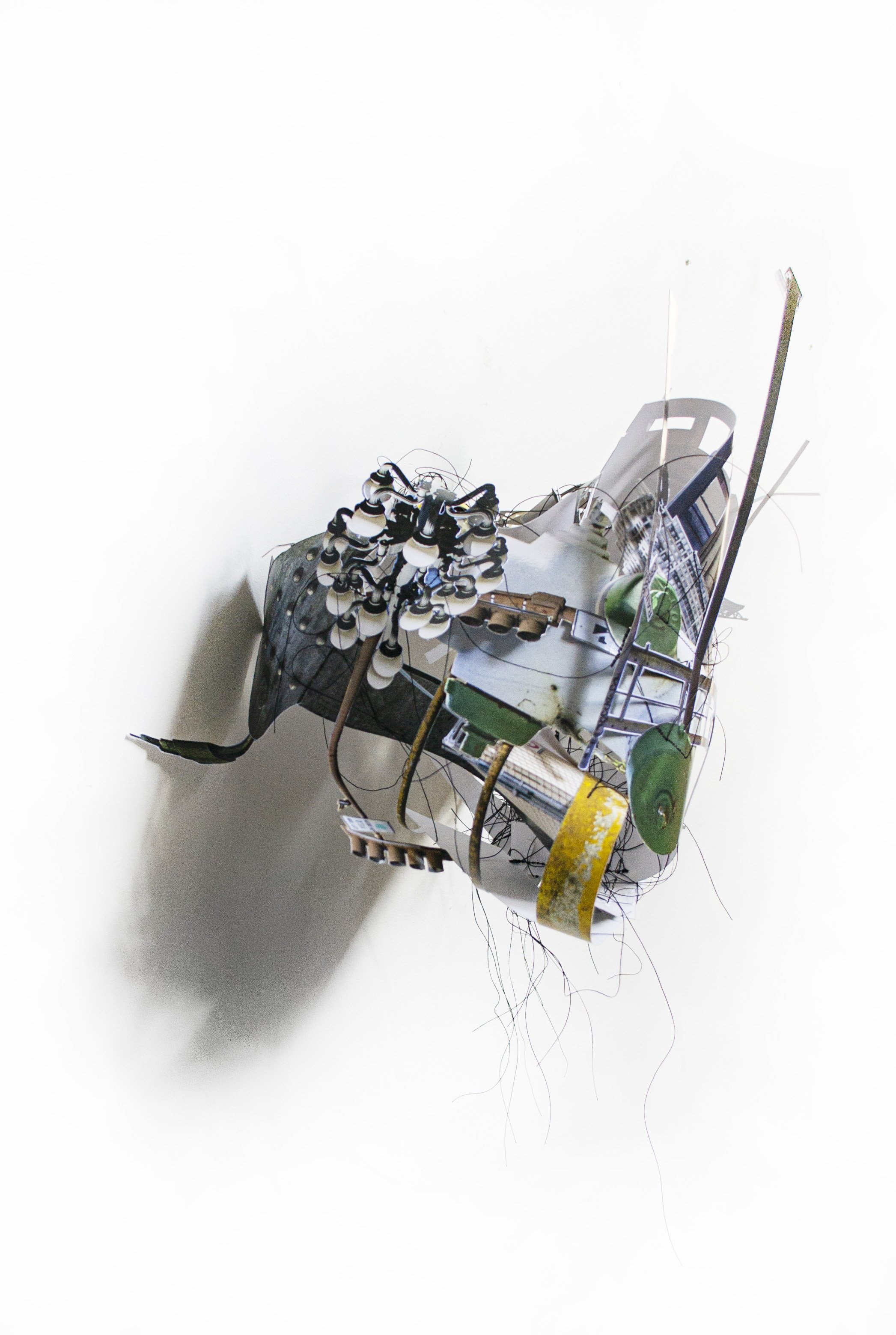

MOMENTOus

In 2022, I deconstructed and reconstructed my past photo-based sculptures to created new, larger scale, hanging objects. All work is hand and machine sewn.

Chaos Control

paper, ink, thread, carabiner, chain

51” x 38” x 34”

2022

Retrod Scrawl

paper, ink, thread, carabiner, chain

44” x 28” x 22”

2022

Scarcity Overflow

paper, ink, thread, carabiner, chain

49” x 42” x 45”

2022

For more installation images and information about this work, see documentation of my recent show, Hedges and Ledgers.

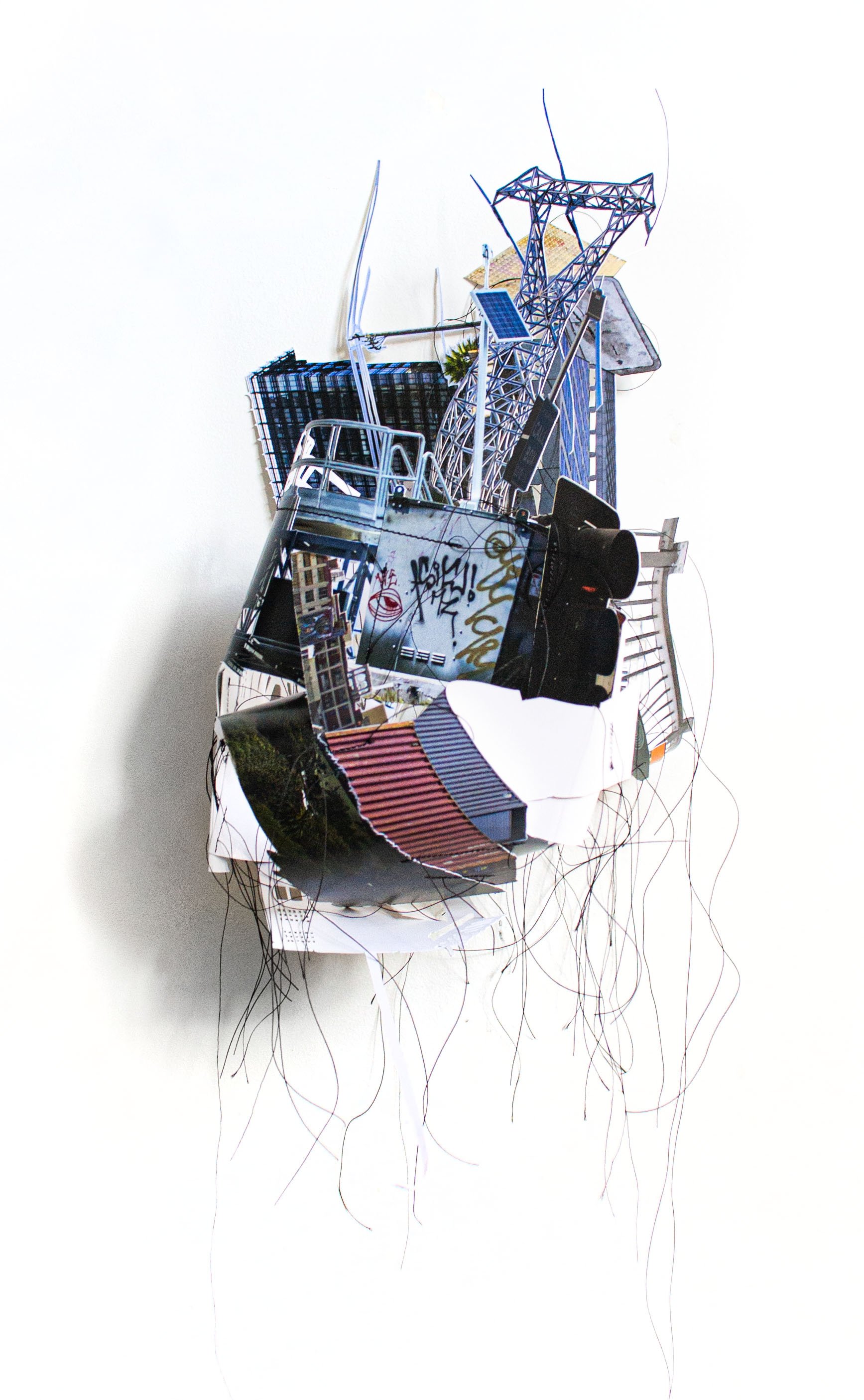

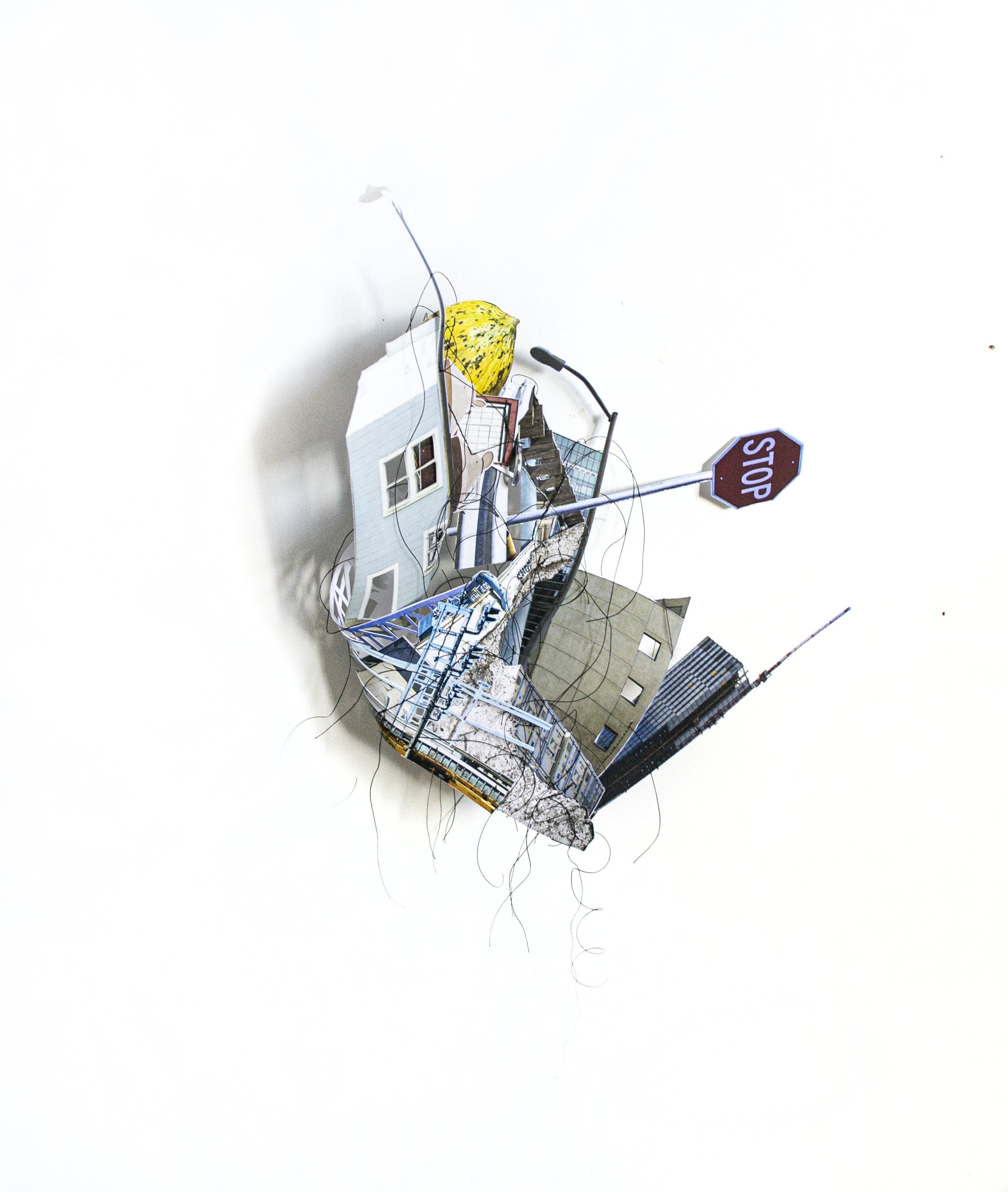

Season First/Finale, Episode Attuned

In series Season First/Finale, Episode Attuned, I have created vignette assemblages for the Likkle Gallery. These objects, made for the wall, act as re-formations of street scenes or what might be hidden in alleyways.

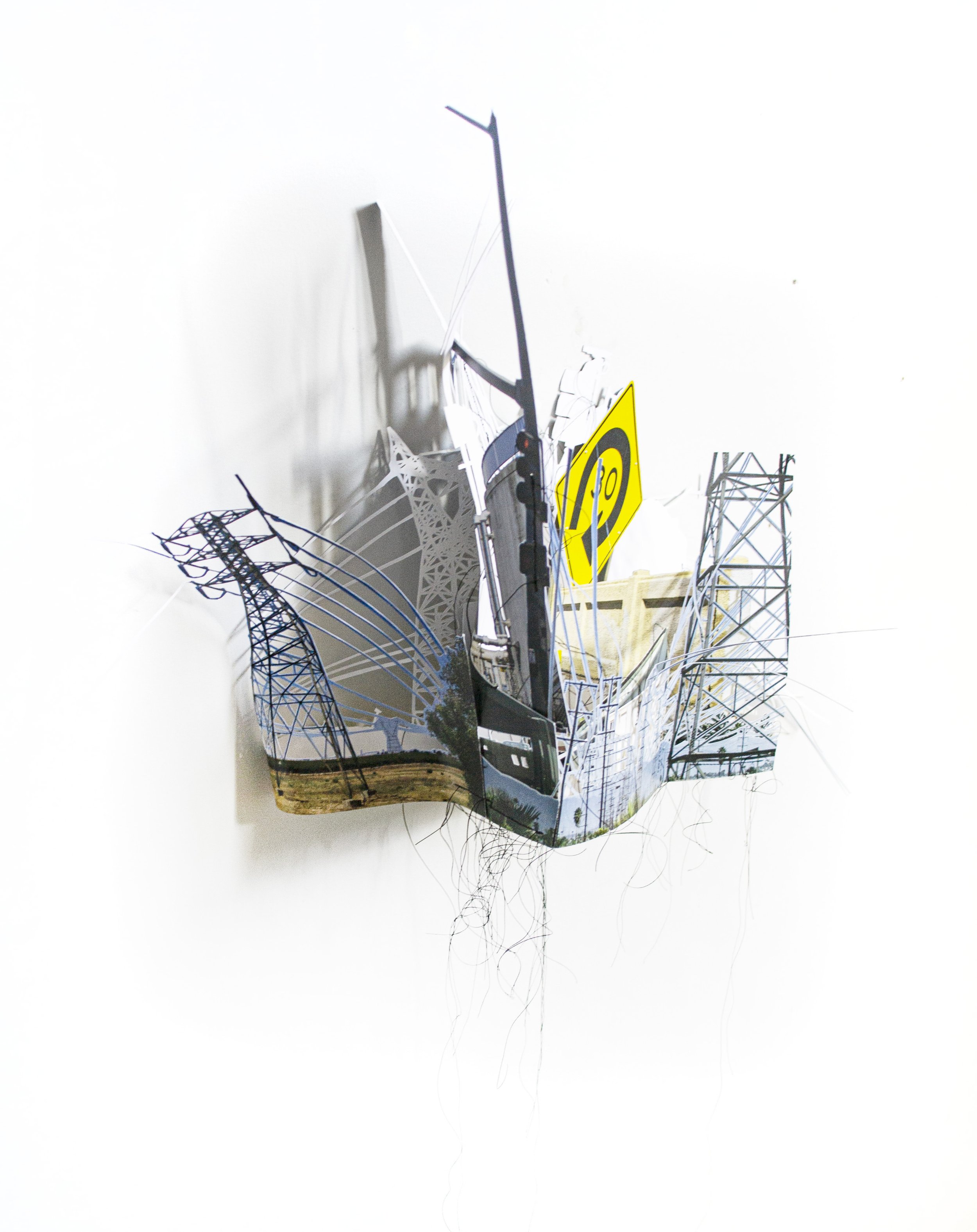

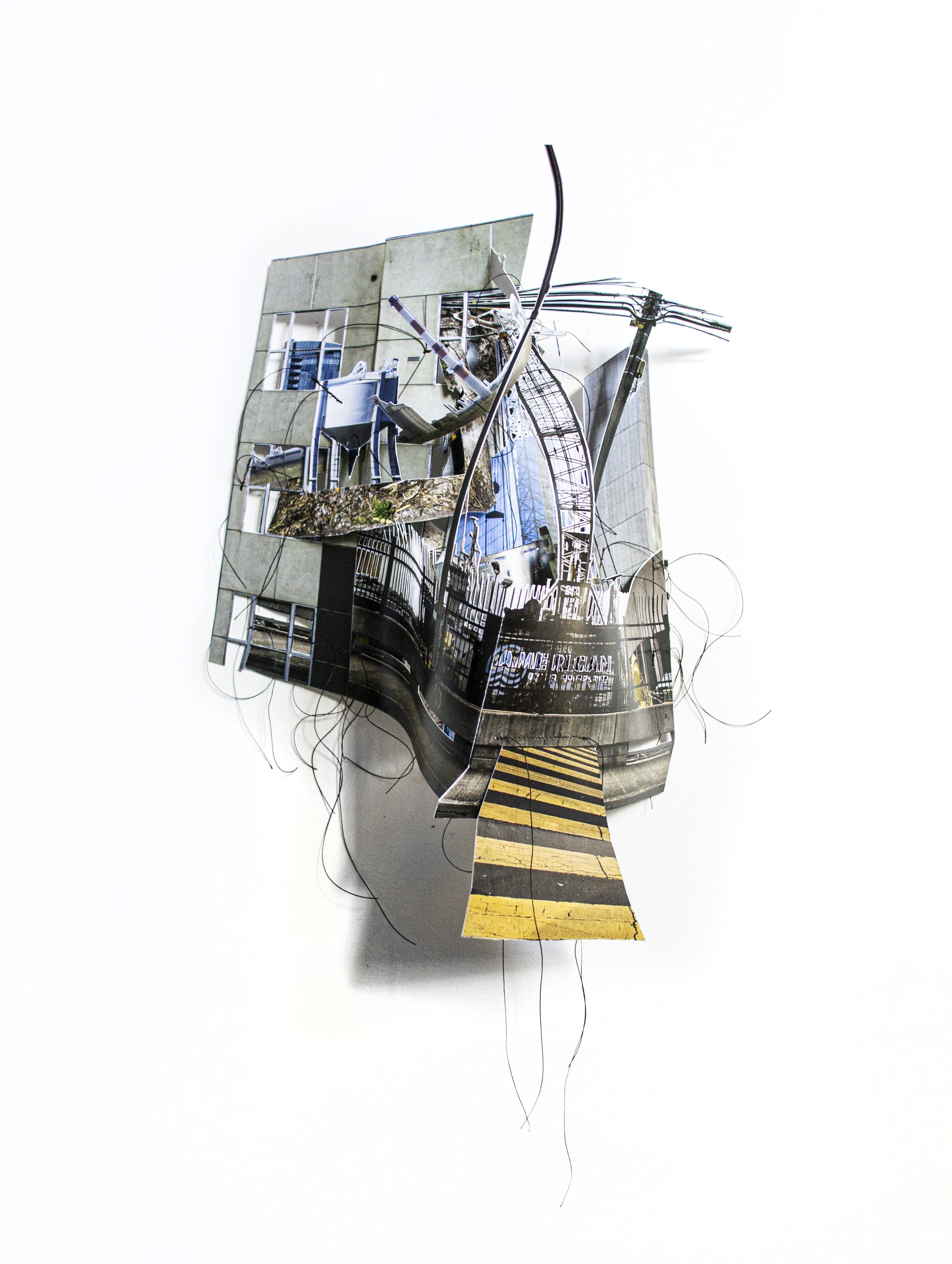

Construct

In 2021, I began Construct, in which I digitally re-install the photo-based sculptures into locations in infrastructural locations in Northern California. These new placements create surreal images that reinforce the need for unprecedented perspectives and approaches in the face of entrenched systems, and, also, add another dimension of scale to the many layers of approaches and places already embedded. Each site spotlights process—the foundational means by which capitalism directs us to accomplish the tasks that make up our lives.

The City of the Pylon (Solano County, CA)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

36” x 31”

2022

No Right Way (Carquinez Bridge Toll Plaza)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

36” x 31”

2022

Home II (Berkeley, CA)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

27” x 36”

2022

Soap and Sake (Fourth St. and Addison, Berkeley, CA)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

36” x 34”

2022

Lost and Found (Port of Oakland)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

36” x 31”

2022

Plat-form (Port of Oakland)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” x 20.5”

2021

Busy Humans (580 California Street, San Francisco, CA)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” x 19”

2021

Re-union (Phillips 66 SF Refinery, Rodeo, CA)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

30” x 13.5”

2021

Many Ways (Interstate 505 California)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” x 16.5”

2021

Room (Berkeley, CA)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

36” x 24.5”

2021

B(r/l)ocker (West Oakland BART)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” x 15”

2021

We Made It (San Bernardino County, CA)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

36” x 18”

2021

Wind Fire Earth (Solano County, CA)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

16” x 24”

2021

Sink (East Bay Municipal Utility District Wastewater Treatment Plant, Oakland, CA)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” x 19.5”

2021

No Need for Speed (Riverside County, CA)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” X 16”

2021

Positionality: Alway In-Between (Los Angeles County, CA)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” X 16.5”

2021

Salty Tracks (Eden Landing Ecological Reserve)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” X 13.5”

2021

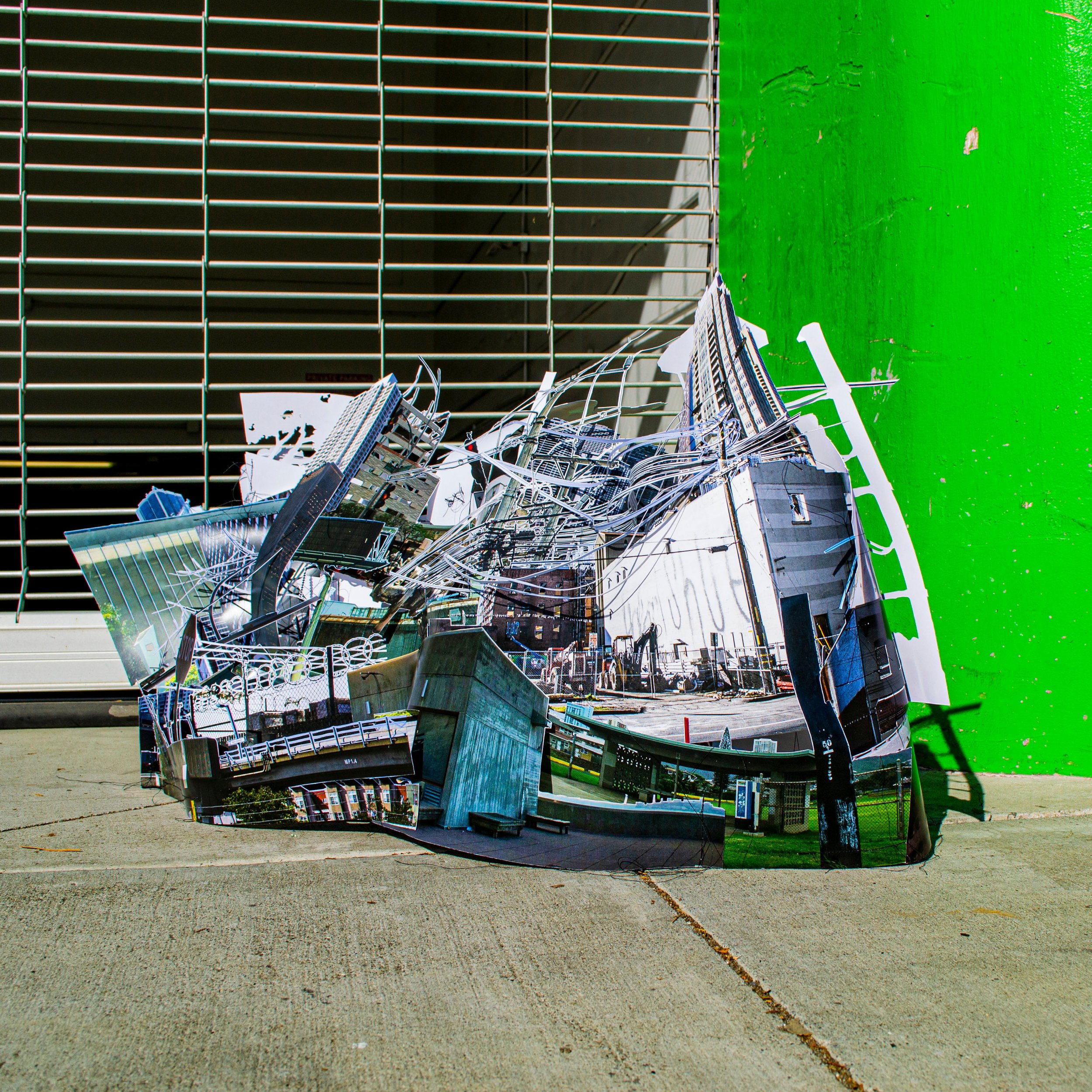

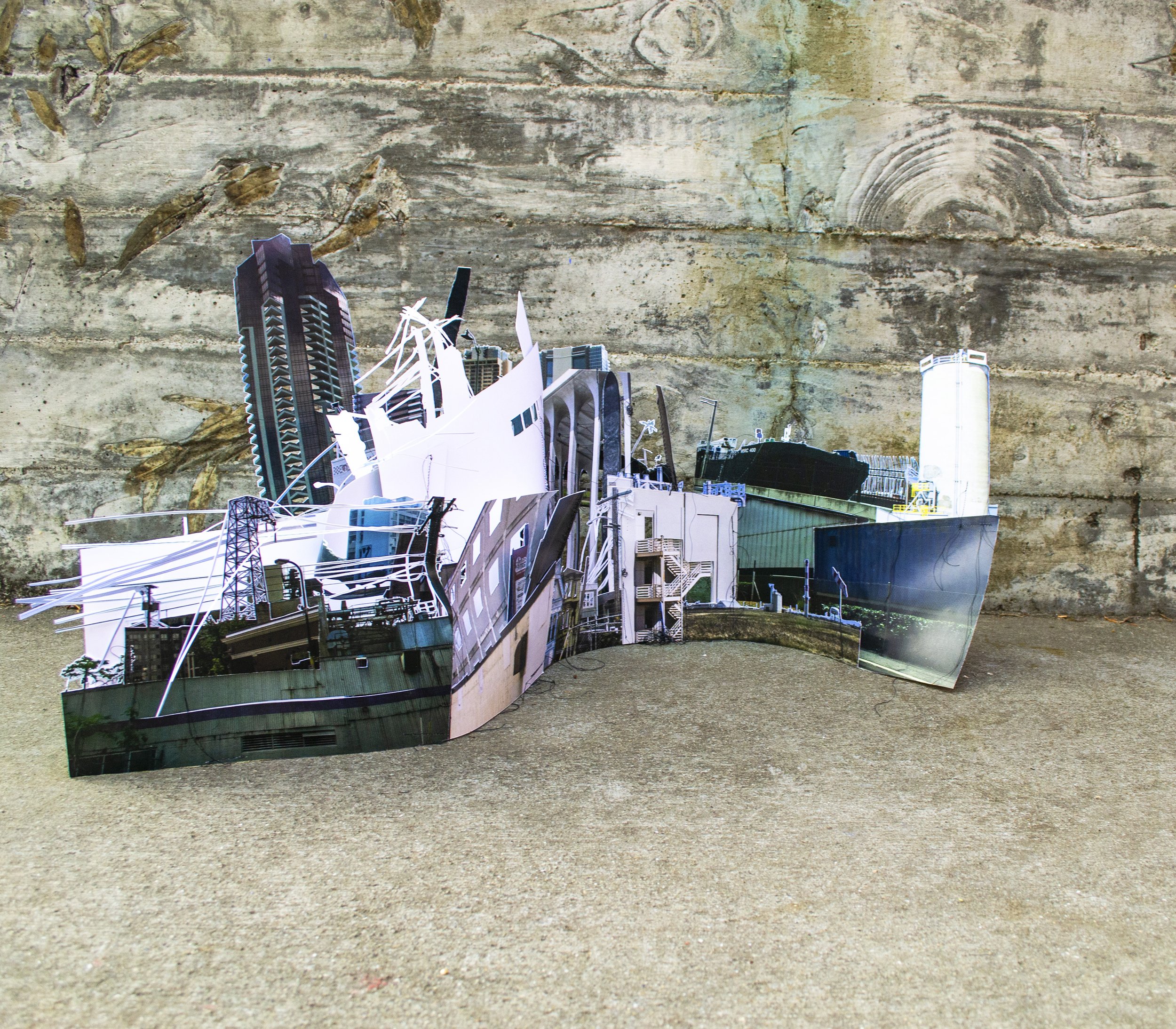

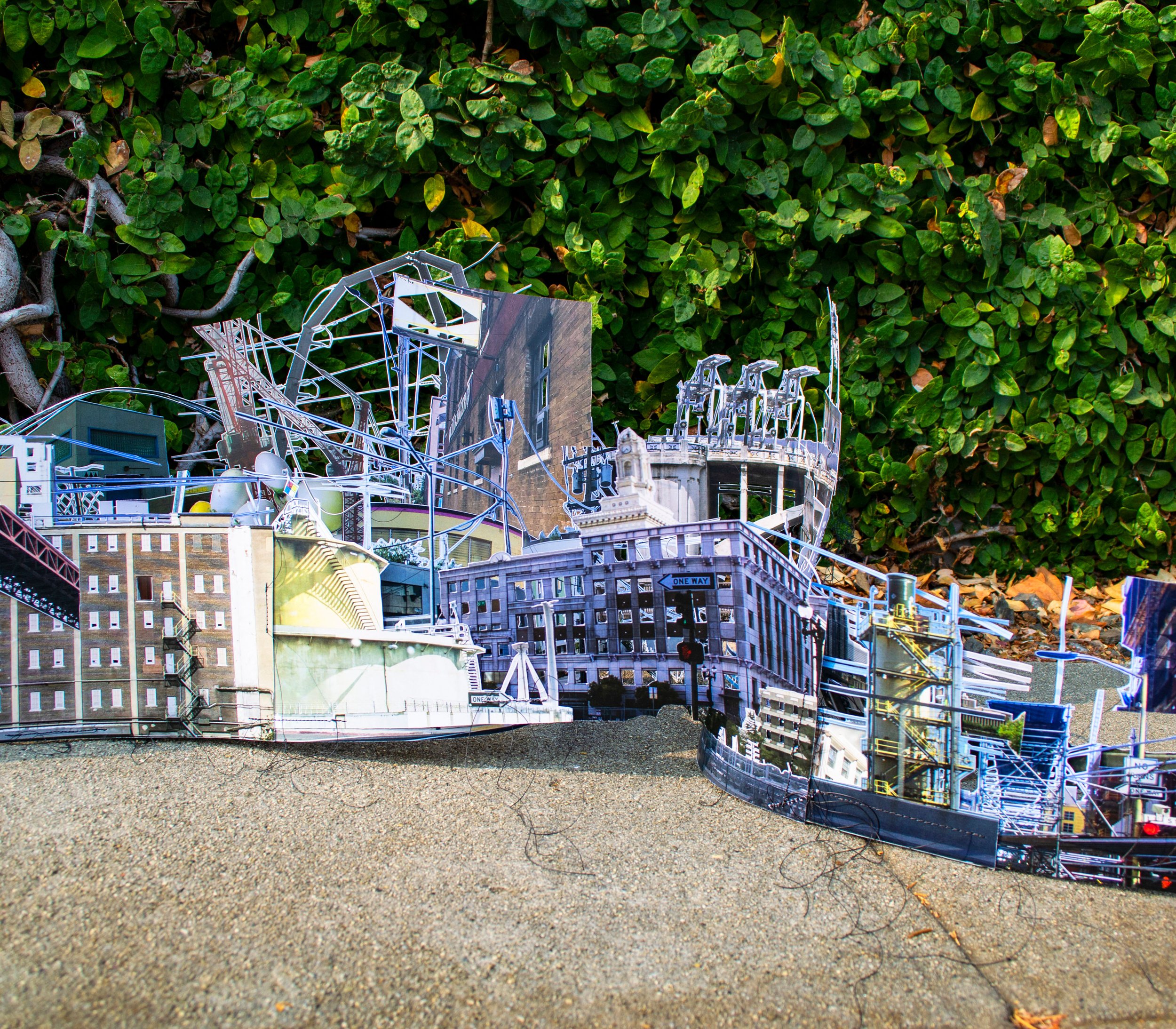

20XX

20XX is a series of photographs of photo-based sculptures, which contort our shared, built environments embedded with histories of society-building through cycles of demolition and consumption. These 3D collages, built through sewing photographs I took in locations in which I have inhabited and visited, visualize our world’s variances in the materials, aesthetics and definitions of shelter; corrosion and states of disrepair; office buildings, factories and mom-and-pop storefronts as markers of personal means of survival and the shells of capitalism's many engines/victims. I then photograph these sculptures in (mostly) public locations in my hometown area, and thus, create my own psychogeographic maps that synthesize and literally locate my privileges and concerns within our mazes of power structures.

Untitled (01/12 2021)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

36” x 32.5”

2020

Untitled (02/12 2021)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

36” x 32.5”

2020

Untitled (03/12 2021)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

36” x 32.5”

2020

Untitled (04/12 2021)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

36” x 32.5”

2020

Untitled (05/12 2021)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

36” x 32.5”

2020

Untitled (06/12 2021)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

36” x 32.5”

2020

Untitled (07/12 2021)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

36” x 32.5”

2020

Untitled (08/12 2021)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

36” x 32.5”

2020

Untitled (09/12 2021)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

36” x 32.5”

2020

Untitled (10/12 2021)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

36” x 32.5”

2020

Untitled (11/12 2021)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

36” x 32.5”

2020

Untitled (12/12 2021)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

36” x 32.5”

2020

Untitled (03/12 2020)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” x 24”

2019

Untitled (04/12 2020)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” x 24”

2019

Untitled (01/12 2020)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” x 24”

2019

Untitled (12/12 2020)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” x 24”

2019

Untitled (05/12 2020)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” x 24”

2019

Untitled (06/12 2020)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” x 24”

2019

Untitled (11/12 2020)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” x 24”

2019

Untitled (02/12 2020)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” x 24”

2019

Untitled (08/12 2020)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” x 24”

2019

Untitled (10/12 2020)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” x 24”

2019

Untitled (09/12 2020)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” x 24”

2019

Untitled (07/12 2020)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” x 24”

2019

Untitled (08/12 2019)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” x 24”

2018

Untitled (12/12 2019)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” x 24”

2018

Untitled (11/12 2019)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” x 24”

2018

Untitled (05/12 2019)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” x 24”

2018

Untitled (01/12 2019)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” x 24”

2018

Untitled (06/12 2019)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” x 24”

2018

Untitled (02/12 2019)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” x 24”

2018

Untitled (03/12 2019)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” x 24”

2018

Untitled (09/12 2019)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” x 24”

2018

Untitled (04/12 2019)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” x 24”

2018

Untitled (10/12 2019)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” x 24”

2018

Untitled (07/12 2019)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” x 24”

2018

Untitled (10/12 2018)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” x 24”

2017

Untitled (08/12 2018)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” x 24”

2017

Untitled (12/12 2019)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” x 24”

2018

Untitled (11/12 2018)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” x 24”

2017

Untitled (09/12 2018)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” x 24”

2017

Untitled (07/12 2018)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” x 24”

2017

Untitled (02/12 2018)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” x 24”

2017

Untitled (01/12 2018)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” x 24”

2017

Untitled (05/12 2018)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” x 24”

2017

Untitled (04/12 2018)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” x 24”

2017

Untitled (06/12 2018)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” x 24”

2017

Untitled (03/12 2018)

Archival inkjet print mounted on aluminum

24” x 24”

2017

For me, this work is primarily sculptural, autobiographical and portraiture. It holds my experience of capturing an environment’s manifestation at a specific point in time. When photographing a place, I am interested in the interaction between human interventions and nature, which themselves are fluid and overlapping. As humans, we are part of and come from nature, such that everything we do and make can be thought of also as of nature. Unfortunately, our creations and desires for control are often harmful both to ourselves and the ecosystem, a core reason we are in a self-harming spiral in which the default perspective centers a false duality of human versus nature. I see graffiti and tents as emotional and physical acts of human survival. I see rusted, dirty and corroded facades as materials—sourced from the earth and manipulated— reacting to the elements, whose patterns are changing because of us. I see development sites teaming with cranes and other Caterpillar machinery as the short window during which the reality of human-controlled and human-sized labor is on display and exemplifying the human power that facilitates our mystified world.

As someone whose main mode of transportation has always been by foot, I have always had a deep connection with the environment around and through which one can walk. Aesthetically, I love sidewalks and roads: they are expansive, collective paintings encompassing different shades, shapes and textures. As a sculptor and a walker, I am drawn not just to buildings but also to the architecture of the streets—mailboxes, telephone poles, fire hydrants, the curb—that add new layers of meaning, color and form to the concrete canvas. Not only are these objects human-scale, they are often on and representations of public property, a (technically) shared space often in a sea of “No Trespassing” signs. They are representations of systems that, in theory, are supposed to serve everyone while in reality, often reinforce our divisions by simply reflecting omnipresent hierarchies.

My drive to understand the emotional and psychological forces behind our individual and collective actions has led me to think a lot about power, control and trauma, which I see clearly in our environments. Power can be thought of as the ability to use and control resources, whether those be material, bodily or psychological. While only a small subset of humans have and do hold power on a large scale, we all, daily, manipulate, interact with, witness some aspect of the physical world to respond to and represent our internal states. What we see, touch, use, navigate around and live within is a reflection, an extension and a portrait of us.

In response to forces of domination and the wounds they inflict, I am very interested in empathy, how to build productive and supportive solidarity within the existence of multiple perspectives, and the reality that one view can include intersectional beliefs and unconscious desires that seem hypocritical or irreconcilable in someone else’s schema. In addition to engaging with individual outlooks on the world, and, especially, how they are formed in relationship to demographic categorization, I am focused on the interplay between systemic results and micro points of view. Our built environments are part of those results. How one is forced to and chooses to navigate the physical reality leads to perspective-building. Thus, variances in scale are key as zooming in and out (visually and philosophically) can create different relationships between, and therefore understandings of, one’s body, objects and context.

I live in the neighborhood I grew up in and even though I may not have had a direct hand in installing or manipulating the concrete, plants, wayfinding signs, I feel that the paths I have traversed thousands of times are part of me. When I think deeply about a portion of a sidewalk on a specific street, I can feel its form, shadows and colors made by a curve in the road, a fence taller than me and trees whose droppings collect in the planting strip. In that space, I can remember instances of walking through it—with friends, alone, at night, etc. At the same time, it is a public space and I recognize and appreciate it holds that space for everyone.

The photographs I take to form the sculptures are both of my hometown area and places I travel to and through, most often to visit loved ones or to return to locations in which memories are deeply rooted. I can feel at home in a place once I become confident navigating it on foot and, especially, once I find a feeling of safety in shortcuting through its parking lots or parks. However, no matter where I am, when on foot, I am conscious of my body’s vulnerability, given its size and perceived gender, in public space. As someone whose experience is that of an outsider to the perceived normal and default identity, but also not an insider to my prescribed racial demographic, I feel ambivalent in many locations, especially those outside of the U.S. My own losses and my own imperialism, by virtue of my ethnicity and nationality, are always on my mind.

I love collecting images of new surroundings, especially focusing on that which connects and affects us all: what we visibly have access to, and the material language, lifespan and histories of cement, steel and wood. I imagine the potential lives, thoughts and feelings of the humans whose labor went into constructing a retaining wall, repairing sidewalks or their own gate, or installing the sheetrock in a building. With a wider lens, we can see the social and commodification webs in which all of us work and struggle to survive and thrive. We must all grapple with the lineages and systems of our landscapes: generations of housing segregation, colonial and imperialist impositions, the shifting of the attention economy from the road to the phone, and the privatization of and power dynamics within utilities.

I meditate on each image as I prepare it for printing, which is handled by a local shop, owned by someone who went to the same high school as me. He is the second generation owner and I remember, as a child, going with my mother to get xeroxes at the store’s old site which was run by his parents.

As I meticulously cut out skylines and separated sidewalks from structures within the prints, I choose to include indicators of time and place and discard imagery that I view as perpetuating toxic power. The collaging process is like creating my own psychogeographic map—I sew together pieces of wayfinding in Philadelphia, scaffolds in Jodhpur, and window frames of Oakland apartments, and am able to remember the physicality and emotions of being in those specific places and moments. Numerous seams eventually create micro-conversations between aesthetics and neighborhoods to form a free-standing assemblage. The juxtaposition of industrial scenes, with shiny knowledge-worker office towers, with structures of all types for sleeping, eating and caring, creates a tapestry of the history of and power dynamics within how we spend our lives. With these sculptures, I highlight structures that seem too big, old and strong to fail but are actually fragile (the cracks are more than visible, they are felt); a world of disparities driven by maintenance of power accumulation via the bring-to-market and consumption cycle; and built environments that model aspirational power-over, thus driving decision-making that ignores the reality of interdependence.

In visualizing new ways of seeing the world, through overlapping, woven and contorted concrete imagery, I offer the complexity and the expansive possibilities of the human mind to go beyond the norms we are born into. To challenge people to see their location from slightly different angles and in the framing of curves, loops, waves. At the same time, I recognize and honor our limitations, especially when fortifying against trauma, isolation and deep fear. Thus, I am often coming back to the power and beauty of time and what that looks like. And, the understanding that there is comfort and survival in well trodden neural pathways.

Adding another layer of place and scale, for many years, I have been photographing each sculpture in various Bay Area locations. The massive heights of some built environments displayed in the sculptures are rooted in capitalist and patriarchal domination. My work seeks to offer a more humble perspective. Images of the sculptures are captured from three inches to three feet off the ground, thus allowing representations of skyscrapers to be dwarfed by real fire hydrants—all of which then culminates in another layer of representation, printed and in pixels. The final views of the composite cities are from the level where everyone must step and in the locations that I call home.

I have used the sculptures of 20XX to create a new series of images, Construct, in which I digitally re-install these sculptures back into specific locations that had been previously printed, cut and sewn to make the sculptures. These new placements create surreal images that reinforce the need for unprecedented perspectives and approaches in the face of entrenched systems, and, also, add another dimension of scale to the many layers of approaches and places already embedded. Each site spotlights process—the foundational means by which capitalism directs us to accomplish the tasks that make up our lives.

The images of 20XX and Construct are printed large-scale and mounted on unframed aluminum to maintain the objectness and sculptural quality of the work. They are also printed in calendars which I gift to more than 200 people in my community. In bringing public landscape into one’s private timeline, I hope to spark thoughts about the complexity and interconnectedness of each person's existence in our collective environments. My community of friends and mentors, collected from multiple periods in my life, may spot their neighborhood freeways or historic buildings interwoven into the many layers. This practice of yearly and mass gift-giving, like many aspects of my assimilation culture, follows a family tradition rooted in Japanese practices of appreciation and reshaped by experiences of both traumas and achievement in the US.